|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

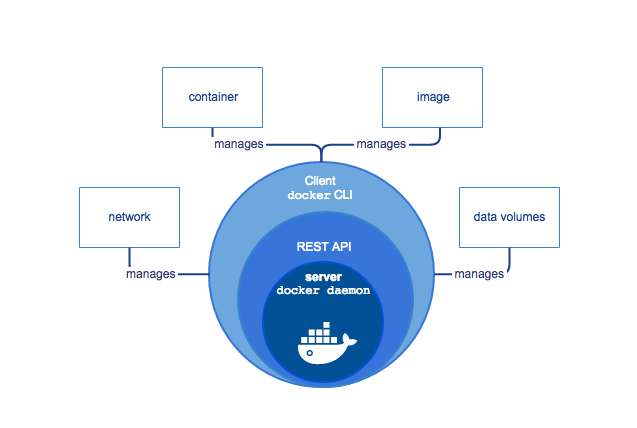

Docker has been used in lots of projects and all kinds of people talking about it. But why Docker is being used? Before trying to judge the usefulness, you should get to know the most important elements and tools around the Docker ecosystem when getting started. Some of the top tech companies like Google, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Intel, Tesla, and Juniper Networks have their own custom version of container engines. They heavily rely on them to build, run, manage, and distribute their applications.

Docker is an extremely powerful containerization engine, and it has a lot to offer when it comes to building, running, managing and distributing your applications efficiently.

A firm understanding of those will make it easier for you to ask the right questions and will help you navigate the sea of Docker stuff without feeling lost.

Container

Imagine you’d like to run a command isolated from everything else on the system. It should only access exactly the resources it is allowed to (storage, CPU, memory), and does not know there is anything else on the machine. The process running inside a container thinks it’s the only one and only sees a barebones Linux distro of the stuff which is described in the image.

That sounds an awful lot like VMs, right? Yup. Only containers start faster and have less resource overhead. The best things about having a web app in containers, in my opinion, are:

- You can get it to run on any Linux distro, given that Docker is installed (Ubuntu, Amazon Linux, …).

- Deploying on a new server is really easy.

- Multiple containerized apps on a single server don’t mess up each other.

- If you update an app, you just build a new image, run fresh containers and don’t have to worry about other ones on the machine breaking.

- Your apps will not break due to OS updates of Docker-unrelated packages. If Docker itself is updated, this will affect the containers. Also, underlying mechanics, such as the system kernel and glibc updates, have been known to cause trouble.

A great way to think about the benefit of containers is the way Docker was originally pitched and introduced — comparing it to the global shipments. Before standardized containers were agreed upon, it was quite challenging to pack and repack stuff along the journey, depending on which vehicle it needed to be transported with (packing boxes into a truck, just to have dozens of people unpack them from the truck and carry them on a ship). With standardized containers, you just lend or buy a container, pack it with your things (in a way that makes sure the container is not negatively impacted, like things sliding around) and from then on people know how to handle the container and don’t need to adjust too much to what’s inside. Huge cranes loading and unloading containers on ships.

It’s the same with Docker containers containing apps. A machine running the container should not have to care about what’s inside too much, and the dockerized app does not care if it’s on a Kubernetes cluster or a single server — it will be able to run anyway. A container can run more than a single process at a time. Some people choose to limit it to one, though. You could package many services into a single container (let’s say Nginx, Gunicorn, etc.) and have them all run side by side.

Images

An image is a blueprint from which an arbitrary number of brand-new containers can be started. Images can’t change (well, you could point the same tag to different images, but let’s not go there), but you can start a container from an image, perform operations in it and save another image based on the latest state of the container. No “currently running commands” are saved in an image. When you start a container, it’s a bit like booting up a machine after it was powered down.

It’s like a powered down the computer (with software installed), which is ready to be executed with a single command. Only instead of starting the computer, you create a new one from scratch (container) which looks exactly like the one you chose (image).

Think of it as a very precise instruction on what operating system to install, what files to put where what packages to install, and what the resulting computer is supposed to execute (a single command) if not told otherwise. Because we are working with data, which is easy to copy, we usually don’t execute all instructions from scratch but just copy the end-state of those instructions (the image).

When starting a container from an image, you usually don’t rely on the defaults being right — you provide arguments to the command being executed, mount volumes (directories with data) with your own data and configurations and wire up the container to the network of the host in a way which suits you.

Dockerfiles

A Dockerfile is a set of precise instructions, stating how to create a new Docker image, setting defaults for containers being run based on it and a bit more. In the best case, it’s going to create the same image for anybody running it at any point in time.

Consider the documentation a project should have. The sections of the README file, telling other people (or you-in-the-future) how to set up the environment, what to install regarding services or libraries, and how to run the project so it does something useful.

Dockerfiles can be seen as the instructions to set up a project — but in executable code. A script that installs the operating system, all necessary parts and makes sure that everything else is in place too.

In a Dockerfile, you usually choose what image to take as the “starting point” for a further operation (FROM), you can execute commands (starting containers from the image of the previous step, executing it, and saving the result as the most recent image) (RUN) and copy local files into the new image (COPY). Usually, you also specify a default command to run (ENTRYPOINT) and the default arguments (CMD) when starting a container from this image.

Volumes

Images don’t change. You can create new ones, but that’s it. Containers on the other hand leave nothing behind by default. Any changes made to a container, given that you don’t save it as an image, are lost as soon as it is removed.

But having data persist is really useful. That’s where volumes come in. When starting a Docker container, you can specify that certain directories are mount points for either local directories (of the host machine), or for volumes. Data written to host-mounted directories is straightforward to understand (as you know where it is), volumes are for having persistent or shared data, but you don’t have to know anything about the host when using them. You can create a volume, Docker makes sure that it’s there and saved somewhere on the host system.

When a container exits, the volumes it was using stick around. So if you start a second container, telling it to use the same volumes, it will have all the data of the previous one. You can manage containers using Docker commands (to remove them, for example). Docker-compose makes dealing with volumes even easier.

Wait, there are disadvantages?

Applications with different operating system requirements cannot be hosted together on the same Docker Host. For example, let’s say we have 4 different applications, out of which 3 applications require a Linux-based operating system and the other application requires a Windows-based operating system. In such a scenario, the 3 applications that require a Linux-based operating system can be hosted on a single Docker Host, whereas the application that requires a Windows-based operating system needs to be hosted on a different Docker Host.

That’s a wrap!

Hope you got some insights into the benefits of using Docker. Since Docker has been used everywhere now, it can be a bit overwhelming. You can learn more about it on their official site.

I have been reading a lot about Docker and practicing a lot. Hope you get the gist of why Docker is so important and why every Developer must learn this.

That’s it for now. See you in another blog.

If this article provided you with value, please support my work — only if you can afford it. You can also connect with me on X. Thank you!